Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater Faces Major Restoration: Inside the $7 Million Fix

An Architectural Marvel Facing Preservation Challenges

Nestled in the forests of Western Pennsylvania, Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Fallingwater is undergoing a $7 million restoration to address structural issues and persistent leaks that have developed over the decades. Completed in 1937, this masterpiece of organic architecture is renowned for its daring cantilevered design over a waterfall. However, its ambitious design and exposure to natural elements have led to various preservation challenges as it approaches its centennial.

For a tall person, visiting Fallingwater can be an unsettling experience. Wright, who stood at 5’7”, designed the parapet walls—the low barriers around the house’s many balconies—much shorter than the 42-inch height required by modern building codes. “The parapet wall on the house’s upper terrace is only 26 inches high, stopping right above my knees,” shared John Matteo, a structural engineer who has worked on Fallingwater since the 1990s. “Under the terrace is a 50-foot drop to the waterfall below.” Yet, despite these concerns, no recorded falls have occurred in the past 90 years, according to Justin Gunther, Fallingwater’s executive director since 2018.

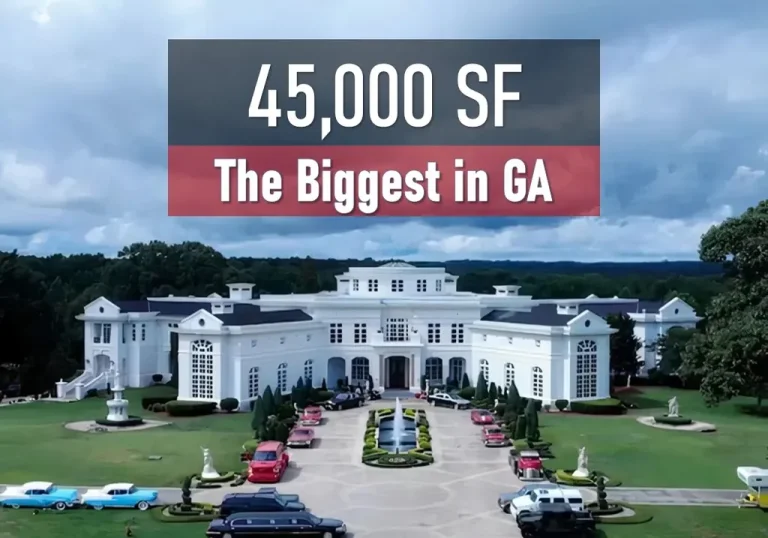

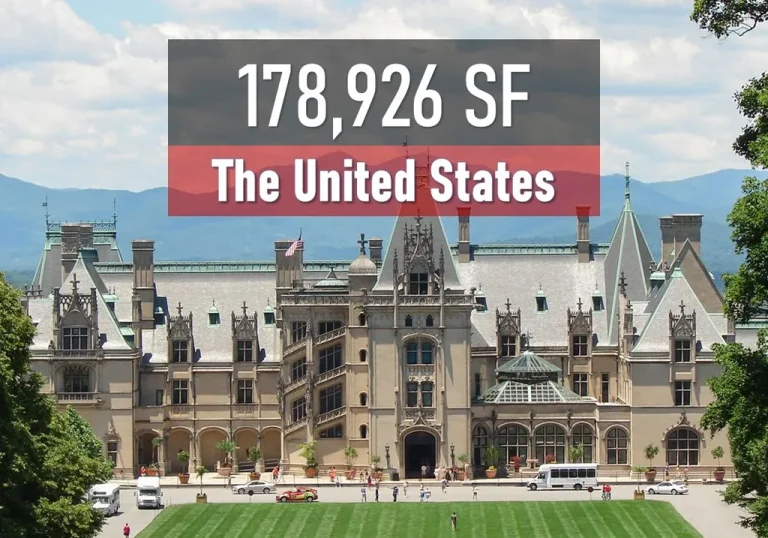

MORE: Celebrity Homes: Inside the Most Luxurious Celebrity Houses in the World

Comprehensive Restoration Efforts

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC), which has owned and preserved Fallingwater since 1963, is leading the extensive restoration project, expected to conclude by winter 2026. The initiative includes:

- Replacing aging roofing systems to prevent leaks.

- Repairing deteriorated reinforced concrete to strengthen the structure.

- Conserving rusted steel windows and doors to improve weather resistance.

- Injecting liquid grout into hollow walls to prevent water infiltration.

“Rain and melting snow have been finding their way into walls that, although they appear to be solid stone, are really hollow masonry tubes,” explained Gunther. When Fallingwater was built, the voids inside these walls were filled with leftover sandstone from construction. However, over 90 years, this material settled, allowing water to collect and seep into the house, threatening its interior finishes, furniture, and artworks. To solve this, engineers scan the walls with ground-penetrating radar, then inject liquid grout through tiny holes drilled into the masonry. Once the grout hardens, the water pathways are blocked, significantly reducing leaks.

Funding and Unexpected Delays

The $7 million budget for the restoration is funded through a state grant from Pennsylvania and private donations, but the conservancy still needs to raise an additional $1 million. Originally estimated at $3 million in 2019, the cost of repairs skyrocketed due to the pandemic and inflation. “The bids jumped to about $6 million, and now we’re closer to $7 million,” Gunther noted.

During early 2024, scaffolding was installed around the house to allow for waterproofing work. However, in February, the scaffolding contractor, BrandSafway Industries of Pittsburgh, became concerned about the force of the waterfall hitting the base of the structure. Work was temporarily halted while the company reinforced the scaffolding, leading to unexpected delays and the cancellation of special hard-hat tours planned for March.

Despite these setbacks, Fallingwater remains open to visitors, with the Preservation-in-Action Tours launching in April 2024, allowing guests to witness the restoration in progress. “Tickets to scaffold-access tours were selling quickly at $89 per person before we had to modify the schedule,” Gunther said.

Did Frank Lloyd Wright Make Design Mistakes?

Gunther believes Fallingwater’s leaks are not signs of Wright’s incompetence, but rather of his bold vision. “He was pushing conventional notions of building to achieve something truly extraordinary, using the best technologies at his disposal,” Gunther stated. However, Pamela Jerome, Fallingwater’s preservation architect, argues that Wright’s resistance to certain waterproofing techniques exacerbated issues.

“At the Guggenheim Museum, we have similar problems,” she said, referencing Wright’s other iconic project in New York City. “One of the biggest flaws was that Wright refused to use copper flashing—a crucial waterproofing element—because he disliked how it looked. As a result, water has continuously found its way into the walls.”

At Fallingwater, engineers are now installing flashing in as many places as possible, although they are opting for lead instead of copper so it blends better with Wright’s original stonework. “Yes, we are overruling Frank Lloyd Wright,” Jerome admitted. “But we are making discreet interventions to help the house shed water more effectively. Hopefully, when we walk away, no one will even notice.”

Structural Issues Beyond Water Damage

This isn’t the first time Fallingwater has required urgent repairs. At the turn of the century, engineers discovered that several of Fallingwater’s iconic cantilevered terraces were sagging significantly. One terrace corner had dropped seven inches, a sign that Wright had used less rebar (reinforcing steel bars) than necessary.

To fix the issue, engineers drilled holes through the concrete beams and inserted high-tension steel cables, a process called post-tensioning, effectively pulling the structure back into place. According to Gunther, the post-tensioning system has performed well, but previous attempts at waterproofing were less successful.

“During the first restoration, we repointed the stonework and applied a water repellent, fixing 59 out of 60 chronic leaks,” Jerome noted. “But over the years, that repellent was washed away, and the leaks returned.”

Fallingwater’s Lasting Legacy

Despite its preservation challenges, Fallingwater remains one of America’s most celebrated architectural landmarks. Named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019, it was voted the most significant building in the U.S. by the American Institute of Architects in 1991. In 2024 alone, more than 143,000 visitors explored the site, reinforcing its cultural and historical importance.

As Fallingwater approaches its 100-year mark, the current restoration aims to secure its future. “We’re doing the best we can,” Jerome said. “But it’s possible that there will always be some leaks.”

For more details, visit Fallingwater’s official site or check the latest updates on Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.